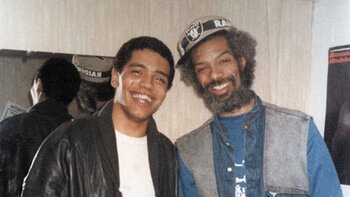

LEGENDARY SINGER and poet Gil Scott-Heron used to introduce Liverpudlian Malik Al Nasir to people as his son.

Malik, then known by his former name of Mark Watson, was more than Gil’s mentee – he was an 18-year-old homeless boy brutalised in care homes before he was mentored under Gil’s wing.

“Gil Scott-Heron saved my life,” Malik told The Voice. “It was the difference between life and death, it was the difference between success and failure, it was the difference between, you know, a life on the streets in destitution, or the lifetime I’m now leading.”

Malik’s journey from an semi-literate and traumatised young man to a poet and academic – who went on to fight and win a case against the local authorities that colluded to keep him in care – all hinges on a gig at Liverpool’s Royal Court theatre in 1984.

Liverpool had experienced an uprising in Toxteth, the historically black district, one of several neighbourhoods to go up inflames in protest at police ‘Sus’ laws and racist oppression.

It seemed the whole of Liverpool’s black community gathered at the theatre to see Gil Scott-Heron, one of the great forefathers of rap. Malik, who was living in the Ujamaa homeless hostel, was desperate to meet his hero.

“So I turned up at the gig with no money, no tickets, and just that sort of desire to get in, but without any knowledge of how I was going to do that,” he recalled.

“And it was just by chance that there happened to be a photographer, Penny, who used to go around Toxteth taking black and white photos, and she’d got a backstage pass. And I was like, ‘Penny, I haven’t got a ticket, I’ve got no money, can you get me in?’ So she told them I was her assistant, and she snuck me in.

“So I ended up getting the prime vantage point to see the whole show from the press pit right at the front. And then

obviously, after the show, because I had the backstage pass, I was able to get backstage and, by twist of fate, I managed to meet Gil and he took a shine to me. The rest is history.”

Gil invited Malik to join him and the band the next day, and was soon travelling with the band doing a variety of odd jobs, from moving equipment to collecting cash from promoters, to checking the sound engineers were doing their job. But his main job was being mentored, and effectively trained, by Gil.

As the years went by, Malik got involved in every aspect of the band, from logistical arrangements for musicians to marketing and understanding contracts.

A crucial moment was when Gil taught Malik how to read. “Initially, much of the work I was doing was verbal, but while on tour in America, Gil gave me something and handed me something to read and asked me to read it out loud, because he was concerned that maybe I had some literacy issues. And when I fumbled, he could see that I was struggling to read.

“I clearly had a lot of issues when it came to reading and writing, and I was obviously very embarrassed and ashamed, because I’d sort of blagged my way, past all of that. You overcompensate with the verbal.

“He then encouraged me to start breaking down words into syllables. It was done over a prolonged period of time, to the point where I then became literate and fluent. But with poetry as well, I got to sort of test language to its limits. And that gave me an opportunity to really extend my thoughts and ideas. It was incredibly cathartic.”

Malik used to engage in sometimes heated debates about political issues with Gil, something members of his band never did. Gil was fascinated with the social and racial issues in inner city Britain, seeing clear parallels with the struggles in America, and he took a keen interest in Malik’s time in the care system.

Collusion

Life took a turn for the worse when Liverpool City Council made a compulsory purchase order on the four-storey family townhouse in Toxteth, which may have been part of moves in the 1970s to ‘dilute and disperse’ the black community.

Malik (then Mark), his siblings, his Guyanese former Royal Navy father and Welsh-born mother were relocated to a predominantly white housing estate in Netherley, on the outskirts of the city, where they suffered racism daily.

He got into regular fights, mostly reacting to racist abuse, and it wasn’t long before the social workers took him away, with the alleged collusion of his ‘nan’ ‘Flo (who it was later revealed was married to his dad) and a local councillor friend of hers.

At the tender age of nine, his first experience of care was a fortnight of solitary confinement followed by nine years of regular beatings at the hands of care home staff.

Malik was kept in children’s homes, such as Greystone Heath, that were later exposed for sexually abusing children.

Bruises

“They used me as a whipping boy to send a message to the rest of the kids. So everyone else would be told, ‘if you don’t want that, you’re going to stay in line’.

“I’m sitting watching the TV and fists would come flying through the air. And next thing, I’m getting booted from one end of the room to the other by a social worker, and I would have no clue why that was happening to me.

“If I had bruises, they would just stop my home leave for four weeks, until the bruises heal.”

Malik would go on to win an out-of-court settlement of £120,000 and a public apology from the Lord Mayor for his treatment.

His life story is expertly chronicled in his book Letters to Gil. Malik, who converted to Islam, is currently studying for a PhD in Cambridge.

He fronts a band, Malik and the O.G’s. Their 2015 album Rhythms of the Diaspora. Vol 1 & 2 features appearances by Gil (who recites Malik’s poem Black and Blue, recorded before the singer died in 2011), plus Jalal Mansur Nuriddin from the Last Poets and LL Cool J.

Letters to Gil is published by HarperCollins, ISBN: 9780008464431, £20, hardback

This interview is just one of many great stories and features in the February edition of The Voice. Much of the stories are only found in the paper, not online. Pick up a copy in your local newsagent, or subscribe here.

Comments Form