“I HAVE NO intention to rest. I’m moving into the most busy period of my life. I definitely hope the best is yet to come.”

These are not words you’d expect to hear from most people in their mid-sixties – then again Basil Watson is far from ordinary.

As our conversation wraps up, Watson’s just as animated as he was at the beginning of our chat – if not more so – with an energy and spark about him of someone decades younger.

It’s half what could be expected from someone with a resume like his, but his wisdom, clarity and eagerness to talk is nonetheless infectious.

Like so many of our elders from the Caribbean, Basil has lived a rich life, and is a natural story-teller. As the grandson of a Trinidadian, there’s a sense of familiarity listening to him in terms of his candour but also the experiences he talks about. It doesn’t feel like an interview. It feels like talking to a family member.

Officially, we are speaking about Basil’s latest and first creation for the city London – something very special indeed, commemorating the Windrush generation – but Jamaican born Watson, is speaking to me from his home in Atlanta, GA in the US. It’s not just where he lives. It’s the location of a breath-taking statue of the great Martin Luther King – one of many masterpieces sculpted by Watson, unveiled in 2021.

As you’d expect, the many months long process of creating it, capturing an icon like King was not simply a job, or straightforward one for Watson having been selected from a pool of talent. It was a culmination of his artistic work thus far.

But when hearing about his early family life and upbringing, which formed the backbone of his character, it seems almost destiny that the 12 foot high figure of MLK in Atlanta, located on a street named after the civil rights hero, would be sculpted with his hands.

“In Jamaica, you’re growing up in a black consciousness society, the people that surround you and the people in important positions are mostly Black. You get a feeling of belonging and that this society is yours and that you can achieve”.

Indeed, striving to achieve is central to his personal ethos. Basil comes from a family regarded as an artistic dynasty in Jamaica- and that’s no exaggeration. His father Barrington Watson, was a renowned and revered painter, whose works are so prolific, that they are widely acknowledged as lifting Jamaica’s global cultural landscape and artistic profile. Basil doesn’t remember watching his father work as a very small boy- but he’s been told he did, often mesmerized by his dad’s work. It clearly had a profound influence on both him and also his brother Raymond, who also ventured into sculpting.

“My father travelled greatly, whether in Europe, North America or Africa. It would be fascinating hearing his stories and seeing the paintings that evolved out of these travels. That was extremely empowering, giving me the feeling that I could be a first world citizen.”

And a first world citizen is ultimately what Basil became. Although his family moved briefly to the United Kingdom when Watson was a small child, he doesn’t have memories of England. His parents moved back to Jamaica following independence, to help the island move towards a new and exciting future. Like his father, Basil’s work has seen him travel the world also leaving his artistic mark.

“My parents’ generation, their mission was to get an education, get a home and provide for their family. The next generation’s task is now to look for leadership in every area of life”.

The leadership mentality passed down from Barrington to Basil, has now spanned three generations. Basil’s son Kai is also a painter. In 2008, both father and son saw both their works exhibited in New York. Art seems part of the family DNA, and central to their lives.

ARTISTIC TRAILBLAZER

Although Basil hasn’t lived in Jamaica for two decades, he has many family members including children who do. Some of his most famous sculptures also have permanent residency in Jamaica. At the national stadium, there are statues of sprinters Merelen Ottey, and Herb McKenley crafted by Watson’s hands. And, a stunning statue of Usian Bolt also in Jamaica created by Watson, depicts the phenomenal Olympic champion striking his famous pose. Bolt described the statue made in his honour by Watson, as one of the “greatest moments” of his illustrious career. That’s not a bad testimony for a CV and portfolio.

Although Atlanta is now his home, Basil’s proud Jamaican identity and early life remains key to who he is, wherever he works, to the benefit of many around the world who enjoy his art. In fact, Basil says, being Jamaican informs every aspect of his life.

“It is the core of what I do. The first half of my life was spent in Jamaica. So when I stepped out of Jamaica I did so with that strong identity of understanding what it is to be Jamaican. I carry the flag, that feeling of us being able to do whatever we want. And being as capable as everyone else.”

Basil’s philosophy seems almost a family tradition or heirloom passed down to him, and passed on by him. His family have helped put Jamaica firmly on the global arts world radar. Their intergenerational impact is reminiscent of another famous family from Jamaica, that helped spark the political consciousness of a generation. The reggae music which first introduced the island’s beautiful genre to much wider audiences, still reverberates around the world.

A NEW DAWN

Fast forward to today, and Jamaica is one of many Caribbean nations pushing for more independence, beyond the period in the 1960s in which Basil’s parents were part of a professional middle class, suddenly thrust into leadership positions charting a new course for the island. Now, following the government’s announcement to fully break from the British crown, the initial drive for independence decades ago is gaining renewed momentum in 2022.

“Ultimately, the world needs to look at lowering borders, we are now world citizens and the world needs to strive towards that view. Britain, France, Portugal and Spain and so on, no longer control the world. There’s also interdependence, we can’t do without each other. But in terms of Jamaica moving away from the Queen being the head of state, I think that that is the right direction for Jamaica to head in”.

The permanent links between Jamaica and Britain, and the significance of the original Windrush generation presented a unique artistic calling and challenge for Basil very recently in his career.

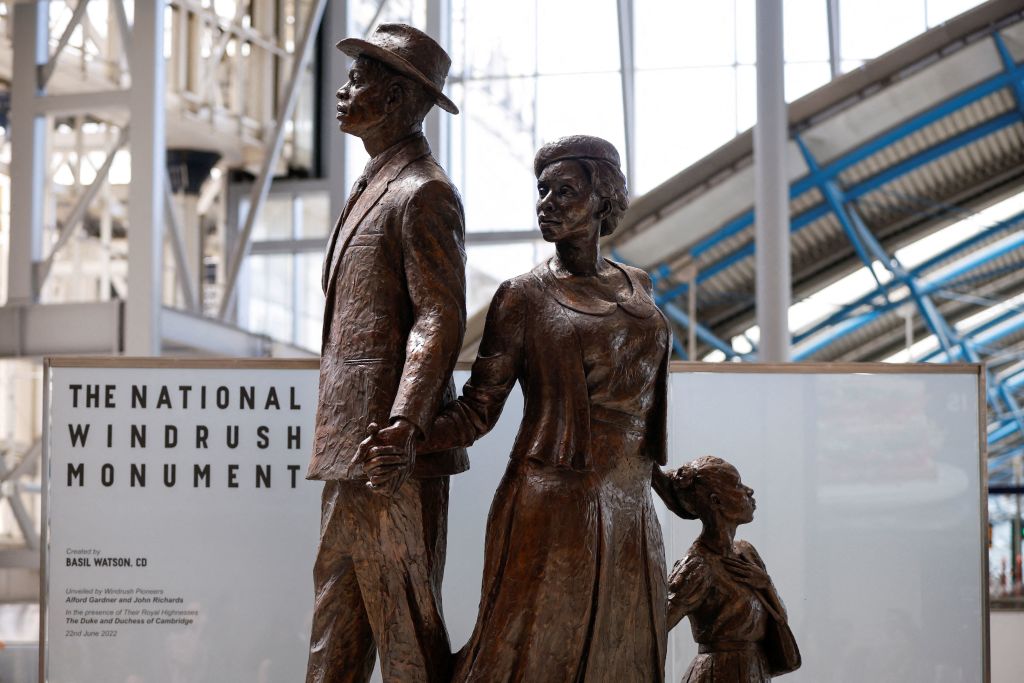

He was selected from a pool of dozens of applicants, to create a permanent monument commemorating the Windrush generation, the achievements of themselves and their descendants, to be unveiled at Waterloo station on this year’s Windrush Day.

HONOURING WINDRUSH

Basil’s design was selected from a longlist of 16 candidates. Windrush Commemoration Committee chair, Baroness Floella Benjamin, then whittled the list down to 4, before the public had their say. Basil’s design was eventually selected as the winner and he was tasked with turning his vision into permanent fruition. No easy feat, given the immense history, and reverence for those who trod before us, and the weight of expectation, to successfully capture the essence of the Windrush generations.

Their spirit, is something Basil says he felt when he created his latest challenge. It created a pressure, but the kind which motivates him – “champagne problems” as he calls them, more than once in our conversation. Even completing the design, something so deeply personal while joyful, also wasn’t easy. “I love it more and more each day, developing as an artist. But this project was hard to let go. Painful even. But the experience enriches me and my character and I carry that to the next sculpture”

When seeing the design it’s not hard to appreciate the magnitude of the task. The statue depicts a man, woman and child, newly arrived Caribbean migrants to the UK, full of hope, dreams, trepidation, uncertainty, adventure and ambition. They stand atop a pile of suitcases, each at a different height representing the original Windrush arrivals and the subsequent generations which came after them. Even coming up and deciding with the vision, let alone executing it to a deadline, seems immensely challenging. How does one sum up all that is perceived to be the Windrush generation?

“I slept on it for about three weeks before I eventually decided on the idea from a number of ideas I had. I wanted to give the feeling of facing a new world, facing a new day and standing strong. The feeling of the mother supportive of the father, and the child feeling confident to take the journey”.

Watson, for me, has captured that sentiment. The suitcase metaphor especially chimes with me, bringing up memories of my own grandfather and other things associated with him that used to conjure up images of the far away land he’d come from and the journey he had been on. This was probably what Basil had aimed for.

“I wanted it to stir emotions, and every emotion. Some will feel joy, some will feel pain – indifference is what I don’t want. I want people to become curious to learn about the experience and what it means”.

I seriously doubt that anyone passing by Basil’s commemoration at Waterloo station in the future that looks at it will experience indifference. He’s clearly poured his heart, soul and being into this project taking time to fill the gaps in his own experience from not really recollecting his time in the UK as a kid, to nonetheless joining the dots and capturing the shared affinity between those who stayed in the Caribbean and those who ventured to the ‘mother country’.

DREAMING OF ICONIC STATUS

For a man of Basil’s experience, what would be his dream challenge? He has sage advice for young people, encouraging them to practice their craft and to always give one hundred percent. But for himself?

“I’m looking forward to more work” he tells me, “The studio is my favourite place. A dream project would be to create a piece that has the iconic status of the statue of liberty, or the statue of Christ in Rio”.

I really wouldn’t be surprised if Basil Watson accomplishes his goal – and sooner rather than later. For someone who has crafted all sorts of figures from sports icons, to MLK, to the Windrush monument, what would be the ultimate message he’d like to convey to the world, through his art?

His answer speaks to what all good art should do ; offer a critique of the world not just as it is, but also a vision of what the world could and should be. “I would like to create something where borders come down, create something that is symbolic with one world”. Thinking about what the Windrush monument will likely mean for so many in marking the achievements of some of Britain’s most important communities, translating a similar message of hope and unity to the wider global arena seems the next logical step for a man who has already trodden big footsteps with his achievements.

Why not a monument for us? ask Big John

Floella Benjamin: Let’s celebrate who we are

‘We were all excited’ – Windrush passenger Alford on his journey

Comments Form

3 Comments

Hey Basil , great artwork in your windrush statue , , it’s a real shame it only depicts the stereotype “windrush “ person and not the minority of people from other countries with other skin types and stories of coming to Britain in the 1960’s and life thereafter .

Her Majesty’s African-Caribbean heritage Subjects have nothing to celebrate on this Windrush Day.

Indeed Voice Reader, all of Her Majesty’s African-heritage Subjects ought to be in deep mourning for our failures in England as an identifiable African-racial group over the last sixty years.

England’s African-heritage people are less organised today, than when the Empire Windrush arrived at Southampton Docks in the 1950s.

We have less political representation today.

We have even abandoned our Saturday Schools.

Our Churches are only interested in Church affairs.

The African-Caribbean people of Birmingham especially have nothing to CELEBRATE.

I was in Birmingham a few years ago when Birmingham City Council was asking the African-heritage residence to organise themselves and restore the derelict Muhammad Ali Centre.

I was in Birmingham when Muhammed Ali came to open the community centre that carries his name in 1983.

To my absolute horror, on a visit to Birmingham in 2010, the Muhammad Ali Centre was derelict.

Birmingham City Council gave Birmingham’s African heritage people a community building.

Muhammad Ali came and open the centre for African-heritage and community benefit.

But Birmingham’s African-heritage residents failed to properly manage the Muhammad Ali Centre.

In the areas I see the Sikh and Hindu Temples looking beautiful and well managed.

But the one building managed by Birmingham’s African-Caribbean heritage people is in ruins.

Today I see Caribbean-heritage people waving flags in Birmingham and celebrating Windrush Day.

We should not be “celebrating Windrush Day,” but asking ourselves why we have completely failed as a racially identifiable African-Caribbean heritage people, to left ourselves mentally and practically as a group from slavery and become a mature; wealthy and organised people.

Wait until the Far right media and there supporters get to know. They be demanding it removing. As it will be classed as WOKE and Destroying White heritage