THE MURDER of Stephen Lawrence and the subsequent Metropolitan Police investigation is a seminal case in Britain’s history of race relations. The case has been of such profound cultural and political significance, not because Stephen was murdered by cowardly white racist thugs, but because the police, the first layer of the criminal justice system, sought to murder Lady Justice; the very justice that Stephen, his family and the wider black community depended on to right such a heinous wrong.

The case that saw the police creating roadblocks to the path to justice has loomed large on the UK landscape like a giant black monolith.

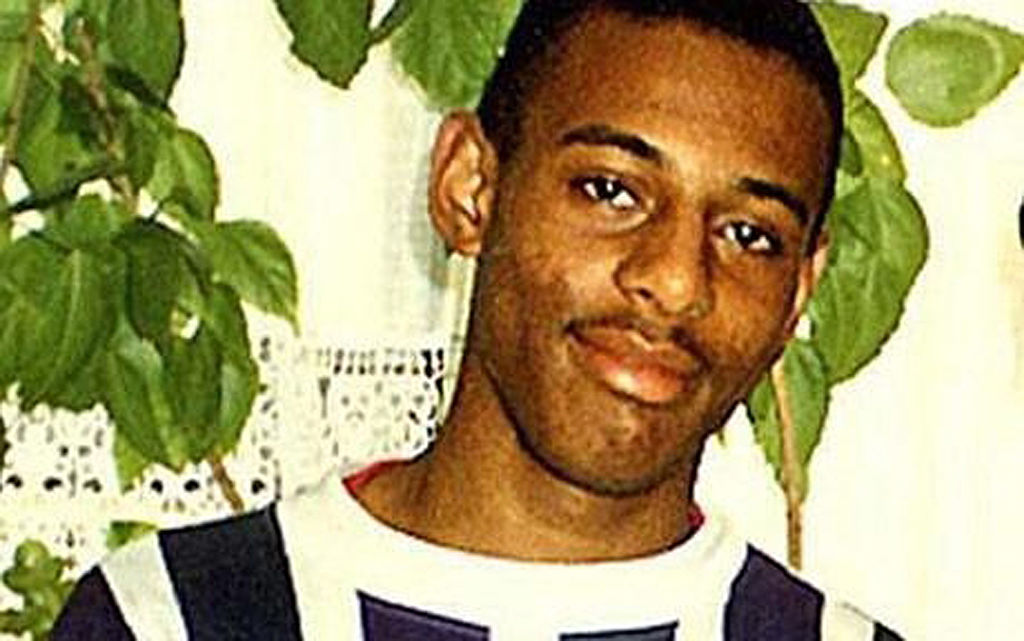

Stephen was a model citizen

By all accounts, Stephen was a model son, brother, friend and citizen, with a very bright future, when on that fateful day (April 22, 1993), he was snatched from this world in a totally unprovoked, ghastly, racist attack that was to send reverberations throughout the UK criminal justice system and in particular policing. I have passed on countless occasions the spot in Eltham, south-east London (a five-minute drive from my home), where Stephen fell mortally wounded.

Each time in the 1990s and early 2000s bar one, I have driven by and literally felt as if I was driving in a Jeep on a safari; “Do not exit your cars and ensure that your doors and windows are locked/closed”.

The feeling of fear, that this was an extremely racist area, would be to put one’s own life at risk

Terence Channer

The feeling of fear, that this was an extremely racist area, where to tread the path that Stephen trod, would be to put one’s own black life at risk. Twenty-eight years later and that feeling, that Well Hall Road is a no-go area, has failed to completely dissipate. The one occasion that I did stop to get out of my car on this infamous stretch of highway (A208), was to gaze poignantly at the memorial marking the spot where Stephen fell as he lay desperately clinging on to the last vestiges of life, no doubt yearning for his mother. They say that dying soldiers who fought closely in hand to hand combat in the world wars called for their mothers — George Floyd called out for his late mother “Momma! Momma!” as his life force was murderously pressed and racially put out.

For decades black people had been treated as second-class citizens in relation to essential services; housing, healthcare, employment, education and criminal justice. Stephen’s death came less than a decade after the enactment of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984.

The Act sought amongst other aims to address racist policing and usher in a new era of police accountability and transparency by sweeping aside the infamous sus laws that had so effectively persecuted young black men, thereby largely contributing to the 1981 UK inner city riots.

It’s a shame that it often takes death and destruction for meaningful change to occur. However, there remained a feeling within the Metropolitan Police (and other police forces) that black victims of crime were not deserving of the same respect, duty of care, investigative integrity and diligence afforded to white victims. Furthermore, the police spying on the Lawrence family and their team’s efforts to hold the racist police investigation to account was egregious and utterly deplorably unforgivable.

I can imagine around that time, when news of the police misconduct reached the Lawrence family, their campaign team and the wider black community, frustration and anger laden conversations taking place up and down the country in black spheres, along the lines of: “Don’t they think that black people matter?!” “Don’t the lives of black people matter?!”

“They just don’t care about black people!” “But black lives matter!”

Sir William Macpherson in his 389-page February 1999 report on The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry concluded that the Met Police was “institutionally racist”. It was a term that Sir William noted had been used in the writings of two black activists, Charles Hamilton and Stokely Carmichael (Black Power: the Politics of Liberation in America, Penguin Books, 1967, pages 20-21). The term has become common parlance. The Macpherson report told us black people what we had known and had been saying all along.

We did not need a public inquiry or Sir William, to tell us that, but we sure welcomed it. Others didn’t.

What has changed since Macpherson?

The current Met Police Commissioner Cressida Dick refuses to accept that her force remains institutionally racist. The statistics on stop and search and use of force don’t lie; I am not going to rehash them. I am tired. The fact that black police officers are twice as likely to be disciplined than white police officers is instructive; even when black people join the ranks as officers we are subjected to racist disciplinary ‘policing’.

Now let’s get this straight; there aren’t institutions without people, people make institutions, people drive institutions. If an institution is devoid of people, i.e. human activity, then it is dead. If the statistics of an institution on stop and search, use of force and deaths in custody disproportionately adversely affect black people, then the institution can fairly and reasonably be deemed institutionally racist.

Stephen’s legacy

Part of Stephen’s legacy is that his case was directly responsible for a significant change in the rule against double jeopardy. This led to two of the accused being retried and convicted of his murder in 2012. I’m not going to say that Stephen was destined to become a cause célèbre, as that would be to undermine his horrific and brutal slaying. In fact, I don’t think it would be irreverent of me to say that I wish I’d never heard of Stephen and the Lawrence family. I would rather he were still here, a 46-year-old, quietly thriving, fulfilling his God-given potential as a fine upstanding black man, maybe a husband and father. I know his family would agree. I can imagine passing him near the fruit aisle in Tesco Lewisham, just another regular black brother doing the midday Saturday shopping with his family. I imagine his wife calling his mother Doreen and saying, “Mummy can I get you anything?”

You see, life is predominately about enjoying the seemingly mundane, the right to have many uneventful yet enjoyable similar days that melt effortlessly from one day to the next, with the occasional excitement, hiccup and surmountable challenge. It is also about the right to life and the confidence and assurance that if this inalienable right is in any way jeopardised, the wheels of a well-oiled colour-blind criminal justice system will be set in motion. Stephen and his family were terribly failed by a criminal justice system that viewed them through the prism of race.

Physics was one of my favourite subjects at school. One of the abiding exercises was the refraction of light through a prism. I marvelled at how the prism split light into the seven colours of the rainbow by dispersion as the light exited the prism. However, the criminal justice system was not intended to refract and then dispense justice; it was not intended to separate or distinguish colour.

That in essence is the Stephen Lawrence story — it highlighted the perverse effects of the colour of criminal justice.

Terence Channer is a consultant solicitor at Scott-Moncrieff & Associates LLP which specialises in police misconduct, injury and healthcare law. He is a passionate anti-racism advocate and dedicates much of his time in this area.

Comments Form

1 Comment

Thank you for this article. I particularly enjoyed the humanity of it and I understand what you mean.

To lose your son in such horrific circumstances then to be so badly let down by the first limb of the criminal justice system is something no parent should endure.

I do not accept that the police are no longer institutionally racist but I fully accept that the police have made changes in Stephen’s name.

I pray that they continue to do so and I pray for their safety as they do a difficult job in difficult circumstances.

I pray for former PM Theresa May who had the wisdom and the foresight to make Stephen Lawrence day a national day to educate all our children and create a kinder fairer society.

Racism is a cancer which impacts those who perpetrate it and those who are victims of it. I pray for those who perpetrate racism and those who are victims of racism.