TUCKED AWAY in a small corner street in Green Park, is a room adjourned with gold frames and the classic curves of French pine furniture, a hazy yellow lamp beams on a grey Thursday morning, and between us just a low-lying mahogany coffee table is where I would meet the daughter of a Black revolutionary.

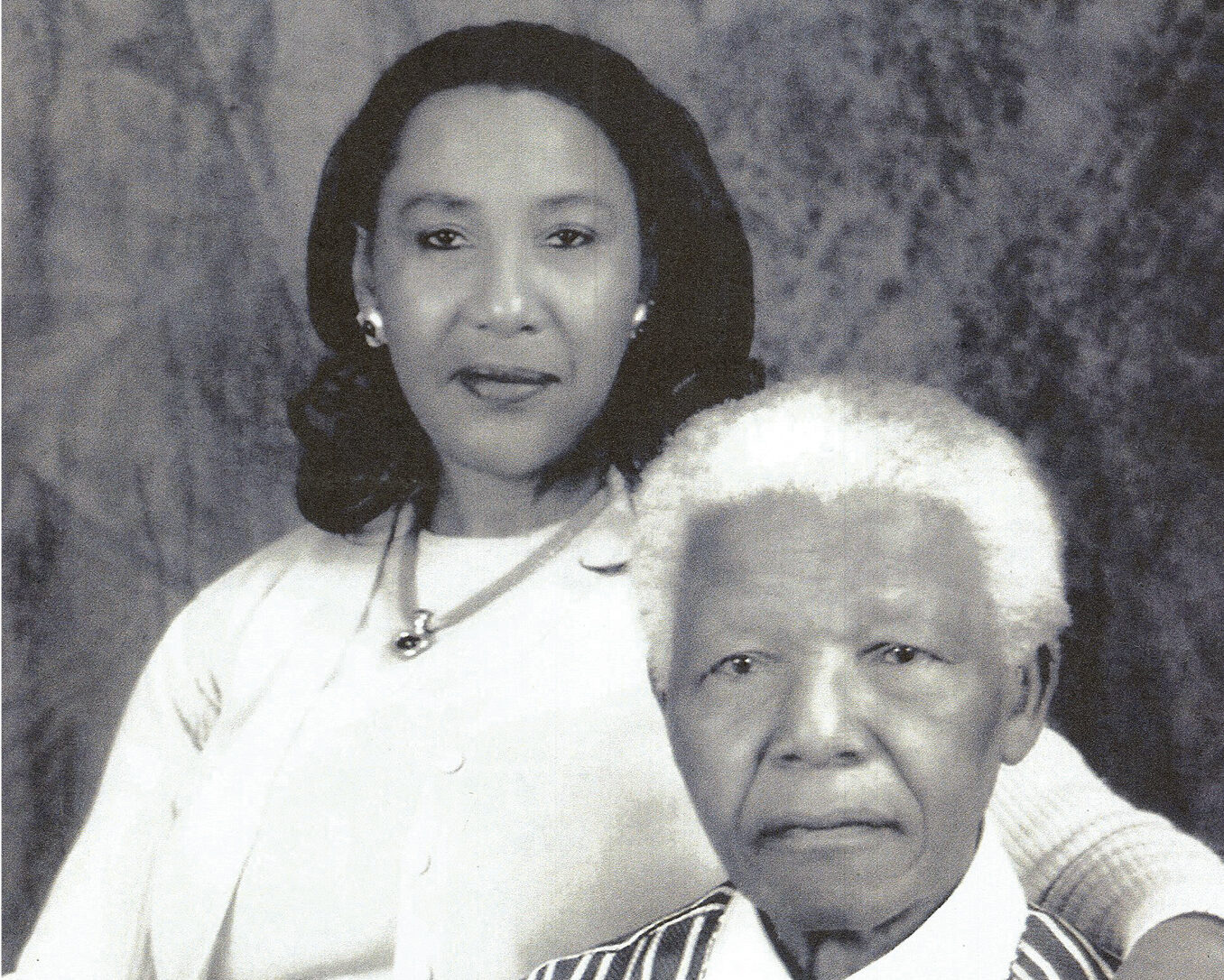

Made up of antidotes and pictures throughout the ages, it’s a visual story of childhoods and traditions, of feats contested and of a simpler life at home in South Africa; Dr Phumla Makaziwe Mandela’s first book about her father is one where she tells his story through his own bloodline. It’s the first, she tells me.

Mandela: In an Honour of an Extraordinary Life is a walk through history that covers both his past and a very present future.

There are opening odes from the Black civil rights leader, the Rev Al Sharpton, Jon van Reenen and Noel Coursaris Musunka who recall how Mandela had a profound impact on their lives.

Dr Makaziwe, also known as Maki, says her own inspiration came from the need to retell a story told a thousand times before.

“A lot of other books have been written about my dad, maybe too many books. But there’s never been a book about him from the family from the children.

“But more importantly, I wanted to tell a different story of Nelson Mandela, not just as a man that fell from the sky and just became this freedom fighter, this great statesman. But a man who comes from a place of his roots.”

Her father’s name was Rohlihlahla Nelson Mandela, a name the world never knew him by. More importantly, his name was “Tata” to his six children (in the Xhosa-language of his people).

Born on 18th July 1918, in the small village of Mvenzo, just 560 miles south of Johannesburg, Dr Maki describes the banks of the Mbashe River that surrounded her father’s birthplace.

A dry and vast land met with endless rolling hills, Mandela was brought up here as part of the abaThembua ethnic group and branch of the Left Hand House of the royal abuThembu lineage, she writes. Mandela wasn’t just Tata, but he was also “Madiba,” most sacredly his clan name amongst the Xhosa-speaking people. As his own father’s life slipped away from lung disease in 1930, his close relative Chief Jongintaba Dalindybeo was entrusted to look after him. Through him, he was meant to be prepared to be the next Thembu King.

Dr Maki says “his character, his attitude, his behaviour, his vision in life” that many grew to admire him for was formed in the little village of Mvenzo through the “traditions, the customs and values of his ancestors”.

“The fact that lineage and kinship was very, very important to my dad, the upbringing and his outlook on life. When he grew up, went to school, even when he fled from the rural areas to Johannesburg, he didn’t think that he was going to be a politician. He was groomed to be an adviser to the kings of the temple.”

Tata did become a politician. He began a Bachelors of the Arts at the University of Fort Hare but was expelled in 1942 after joining a student protest. He later completed his degree at the University of South Africa and later studied law. Tata was behind the opening of the first Black-owned legal practice in Johannesburg.

In his own book, Mandela admits he couldn’t “pinpoint” the exact moment in which he became politicised.

At the dawn of Apartheid in South Africa in 1948, when racist laws in the land became solidified, Mandela was already a member of the African National Congress (ANC), working to create human rights for Black South Africans.

In his courageous fight for freedom, he was sentenced to life imprisonment for 27 years for conspiring to overthrow the state. His time behind walls was split between Pollsmoor Prison and Victor Verster Prison, but most notably on Robben Island.

When she was 16-years-old, she recalls how she applied to the prison commander to see her Tata, sometimes there were no dates available.

“I was very angry, and bitter growing up that I had a father who was there, but really never a presence in our lives. “So I went to visit him when I was 16 and thought we could sit like I’m sitting with you,” she says.

“And that was not to be. We kissed on the glass window. We had intercom phones to speak through and 30 minutes after travelling for over 12 hours by train to Cape Town.”

On Robben Island, she writes that Tata and other prisoners were encased in cells with no furniture and slept on straw mats on the concrete floor. It took seven long years of letters to officials in Pretoria before they were given beds. There was no running water and they used metal buckets as toilets.

She was disappointed every time, Dr Maki tells me, but at least she knew her father was still alive. She wrote letters to him, and he would write letters back, sometimes missing the sentences and paragraphs of a South Africa entrenched in a deep chasm. Sometimes, he also drew pictures of Robben Island.

It would be 27 years until Dr Maki and her Tata were reunited following the culmination of the “Free Nelson Mandela” campaign and the induction of a new South African leader. It was decades of political, social and structural change that brought a raging Apartheid South Africa to a near halt.

Mandela would go on to become leader of South Africa and continue to pioneer for Black and white South Africans to live amongst each other, because believed he was never free, until all South Africans were free. His death at the age of 95 in December 2013 marked the end of an incredible life dedicated to activism, but a new beginning for South Africa.

“My dad started from very humble beginnings and he set himself a goal. He made a very difficult choice to leave your family, to leave your children, and basically be married into politics and the freedom of Black people in South Africa,” she tells.

“In the world, he learnt from other people and the greatest lesson that I’ve learned is that change starts from the inside, we have to know who we are, as a people my father lived his life very authentically. He didn’t stand on a tall building and say, ‘My followers follow me – he just acted.’”

The morning has turned to noon and a grey sky slightly lifted, a hazy yellow light still beams. We stayed and chatted for a few minutes about our impending days, and the ongoing work of Black activists presently and how the work still needs to continue throughout the diaspora.

Mandela: In an Honour of an Extraordinary Life is the bedrock of it all. It’s a final tribute to Tata and all that is to come.

- Mandela: In an Honour of an Extraordinary Life is by Dr Phumla Makaziwe Mandela and is published by Rizzoli (£57.50)

Comments Form

1 Comment

African leaders, instead of creating a creed against slavery; colonialism, and the skin-colour injustice we have experienced, and endured for the last 500 years.

African political leaders, always adopt Communism, and Marxism, as our remedy for the skin-colour injustice, we have historically endured in South Africa, and under Western Caucasian colonial leadership.

Most African leaders, including President Mandela, have used Mr Karl Marx’s political creed; a creed designed to defeat Western Caucasian “class conflict,” rather than an authentic African creed, designed to defeat skin-colour injustice.

President Mandela surrounded himself with Caucasian Communists, and Marxists of every shade.

President Mandela enacted policies which helped the Caucasian wealthy, whilst ignoring the African majority.

When President Mandela came to political office in South Africa in 1996, electricity power cuts, and rampant crime were unknown in South Africa.

South Africa, before African rule, was orderly, with a strong economy.

Today, under African Marxist inspired political leadership, South Africa has reverted to being a failing third world country; with failing, and unworthy African political leaders.

President Mandela’s behaviour in political office was in line with most African leaders today; who enrich themselves, whilst their nation drifts into the economic miasma of a banana republic.