HISTORIANS AGREE that by the 19th century Black demographics throughout Britain ranged from 10,000 – 20,000 people, out of a general population of nine million. Estimates are that at least 10,000 lived in London, with a further 5,000 across the country.

Their numbers would have swelled when Black soldiers and seamen settled in London between 1792 and 1818 after being discharged following the Napoleonic wars.

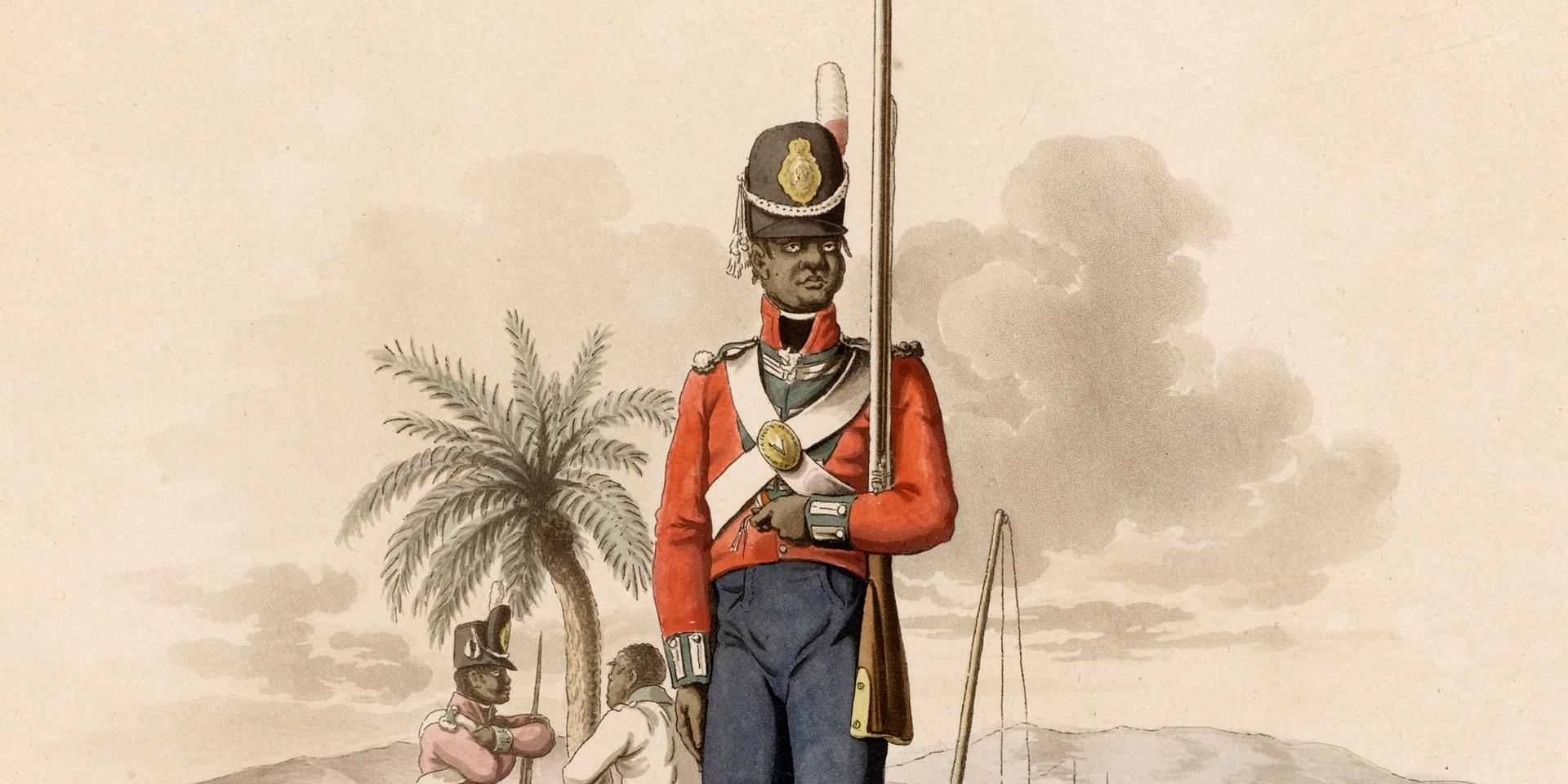

Black soldiers based in Britain were a component of the British army for a long time and, during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the army actively sought them.

Individual Black soldiers fought in many of the Napoleonic war campaigns, including the Battle of Toulouse, the Peninsular War, Quatre Bra, and the final battle to defeat the French emperor Napoleon at Waterloo in June 1815.

While most came from the West Indies, reflecting the slave trade, others came from Africa, the US and Canada, the East Indies, Britain and Ireland.

Black soldiers served in the 88th Regiment of Foot in the Peninsular campaign, and even after the Napoleonic Wars the regiment continued to recruit Black soldiers.

Some were British born, as Black people were being born in such ports at Liverpool at that time. Both before and after the Battle of Waterloo, amongst other regiments, Black individuals were in the 13th Light Dragoons, the 10th Hussars and the 88th Foot.

During the late 18th and 19th century, Britain’s maritime ambitions caused dockside communities of West African sailors to spring up in Liverpool.

These sailors were crews on merchant ships which Britain relied on to transport goods and people from colonised West Africa to Liverpool.

Shipping companies like the Elder Dempster Line in Liverpool began replacing white British sailors with West Africans during these voyages, eventually using wholly West African crews on voyages between Liverpool and West Africa.

They were employed in the engine rooms as firemen, donkeymen and greasers, and were also used on deck to load and discharge cargoes in West Africa.

Various different groups of West Africans worked on Liverpool ships, including Gambians, Gold Coasters (now Ghana), Sierra Leoneans, and Kru people, originally from Liberia. Many of these West African seamen who arrived in Britain between the 1880s and 1920s settled, became permanent residents, and married local British women.

In 1919, a series of race riots broke out in some of Britain’s port cities, including Liverpool, Salford and Cardiff. The race riots took place between January and August and were sporadic throughout the year.

West Africans and West Indians who had lived and worked in the country for many years and served in WWI were attacked by angry white mobs of unemployed sailors and servicemen. Black people bore the brunt of the blame for the violence of 1919 even though they did not initiate the violence and merely tried to defend themselves.

Liverpool, well known for its Black population, experienced the most ‘ferocious and sustained’ rioting in June 1919. Police arrested dozens of rioters.

White rioters killed Charles Wootton, a young Caribbean man. Liverpool’s rioting crowd reached up to 10,000. Out of fear for their safety, 700 ethnic minorities were temporarily removed from their homes and sought police protection.

Black workers were fired during the riots and their homes and businesses damaged or set ablaze by rioters. The government often did not reimburse victims for property damages and did not challenge the attitudes and violence of those who attacked them. Instead, the uprisings of 1919 led to government calls for legislation to repatriate Black people back to West Africa.

Racism, post-war economic hardship, and the reclassification of Blacks and others along with the 1920 and 1925 immigration mandates, all made life difficult for Blacks particularly in seaport areas after the 1919 riots.

Despite these huge challenges and opposition, some 19th-century Black people living in England achieved great success.

Born William Darby in Norwich, Pablo Fanque, whose father was African, rose from abject poverty to become an equestrian performer and owned one of Britain’s most successful circuses during the Victorian era. He is immortalised in the lyrics of The Beatles song “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!”

Another famous Black Briton was William Davison, a conspirator executed for his role in the Cato Street Conspiracy against Lord Liverpool’s government in 1820.

Nathaniel Wells, the son of a slave from St Kitts and a Welsh slave trader, became Wales’s first Black high sheriff in 1818.

Montaz Marché, a historian and researcher at the University of Birmingham, has uncovered over 100 Black women in London and the southeast in the 18th and 19th centuries, including Chichester, Bristol, Westminster, Middlesex and Southampton. Women held diverse roles in society, including as servants, property owners, wives, and traders.

Marché estimates that Black women would have numbered around 5,000 in the country at this time. Among them were Mary Prince, who became the first woman to present a petition to the Houses of Parliament in 1829.

During WWII men and women from the Caribbean and West Africa arrived as wartime workers and servicemen in the British army, navy and air force. Recruits from the West Indies numbered in the several thousands. Almost 6,000 Caribbean people served in the Royal Air Force, with around 350 employed in munitions factories.

Around 700 lumberjacks from British Honduras (modern-day Belize) were employed in the forests in Scotland. Separately, 40,000 people from the Caribbean were recruited to work in the USA during WWII.

Over 370,000 Africans also fought for Britain. They came from West and East Africa and served in several locations in WWII. Large numbers of troops from both East and West Africa served as part of the South East Asia Command fighting the Japanese.

Some of these Caribbeans and Africans would have settled in Britain and contributed to the country’s substantial Black presence well before HMS Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury in 1948.

By Shirin Aguiar

Comments Form

1 Comment

Really good to know Thank you.